Capitol Architectural Report, Block 8 Building 11 lot 00Originally entitled: "The Reconstruction of Williamsburg's First Colonial Capitol, 1928-1934: A Critique"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1137

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

TO: Capitol Research Group

FROM: Carl Lounsbury

SUBJECT: Whither Capitol Research and Reinterpretation?

Last week members of the Research and Architectural Research Departments and the Foundation Architect discussed the results and implications of the enclosed paper on the reconstruction of the first Capitol. As you will see, I argue that the design and reconstruction of the Capitol in the early 1930s by the firm of Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn was fundamentally flawed.

Mistakes in reading the documentary and archaeological evidence led the architects to reconstruct a building quite out of harmony with their colonial predecessors' intentions. Foremost was a shift in the central axis of the building, resulting in the misplacement of the principal east-west doors and windows. The ramifications of this error was far reaching. The passage through the building from one wing across the arcade to the other and the patterns of circulation within the General Court and House of Burgesses cannot now be corrected without major alterations to the building.

Another problem, one that can be seen in retrospect as almost inevitable, is the over elaboration of the interior furnishings and woodwork. For example, a misreading of a 1703 specification led the restoration architects to fully panel the General Court (with carved pilasters thrown in for good measure) where only a small section between the justices' bench and the circular windows in the apse was to be wainscoted.

After reviewing the paper, the various members present sorted out the philosophical dimensions and practical dilemmas posed by its results. The group debated the idea of tearing down the building and reconstructing the second capitol. As the architects had done in the 1930s, they rejected this proposal since so little is known about this latter building in which the events of the Revolution took place. It now seems apparent that we do not even have an early illustration of this building before it burned in 1832. Less extreme, but just as costly would be to rework the present building to make it conform to its known early eighteenth-century appearance. This would be no small tinkering with furniture or decorative trim but would almost invariably involve a major if not complete face lift. Nearly all the exterior brickwork would have to be removed, new door and window openings constructed, the interior set of arches in the connect- 2 ing arcade removed, and a complete refitting of more appropriate early eighteenth-century woodwork throughout the entire building.

Estimates of such a capital campaign ranged from 10 to 25 million dollars. A number of members questioned the ethical value of spending such an exorbitant sum for one project. They noted that even if we got the architectural setting right, we would still face the anachronistic interpretative problem of explaining the events of the American Revolution in the wrong building. Secondly, such a commitment of sums to this one project might be better served in any number of other research programs and physical reconstructions or restorations.

A second approach would be to admit that the capitol has many major problems but make a number of alterations that would serve to rectify some of them as well as enhance the interpretative program. Following this line of argument, it was suggested that in order to incorporate the theme of an expanding bureaucracy and the transformation of provincial government in the years from 1705 when the capitol was completed to 1747 when the building burned, we could make some slight changes to the building that we know occurred during this period. For example, the chimneys that were inserted in the north wall of the capitol in 1724 (see the Bodleian plate), the expansion of the seating for the increased number of Burgesses in 1727, and the replacement of the circular windows in the apse with sash windows in 1730 would allow us to discuss the changing role of government institutions over a longer period of time as well as bring the storyline closer to the period of the Revolution. If we interpret the capitol to the 1740s rather than when first built in 1705, we will be able to make sense of anachronistic elements such as the mid to late eighteenth-century woodwork and the c.1730s Speakers Chair in the House of Burgesses. Although these modest changes would provide substantial interpretative benefits, they would still leave us with many unsolvable architectural problems.

The last alternative would be to leave the building along and continue with the schizophrenic problem of narrowly focusing on the events of the Revolution in the wrong building--wrong historically, and now known to be wrong architecturally thanks to the mistakes made in the 1930s reconstruction.

No matter what we ultimately decide to do, everyone agreed that much more research needs to be undertaken. It was pointed out that archaeological investigations should be under-taken in the capitol yard and areas around the capitol where fill and other stratigraphic artifacts could tell us something about the appearance and function of the two capitols and associated ancillary structures. As John Hemphill's recent research has shown, much still needs to be done to understand the daily activities and functions of the various offices of provincial 3 government. A major study of provincial documents may yield much useful information concerning the location and artifacts of the personnel who occupied many of the offices in the capitol.

It was agreed that any architectural changes that might be contemplated need to be thoroughly analyzed in light of the historical documents associated with the capitol as well as major government buildings in America and England. As we discovered in our research on the Williamsburg courthouse, both details and overall patterns can be best understood by comparative analysis.

It is estimated that archaeological, historical, and architectural research would take several years of work and require a substantial commitment of funds.

Finally, the group thought that we could make excellent use of the Public Records Office to develop a major architectural and historical exhibition of provincial government in colonial Virginia. The research undertaken for this project could be displayed in one or two rooms of the office through drawings, models, paintings, and other artifacts. One way to partially solve our dilemma about the flawed reconstruction of Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn would be through a series of detailed drawings and models of the capitol as reconstructed, as it should have been reconstructed, and how it appeared when it was rebuilt in the 1750s. With these architectural elements, including any useful fragments preserved in our archaeological collections, we could incorporate the paintings of the patron saints of the Revolution who now hang anachronistically in the capitol.

If there is room in the building, a further dimension of provincial government which is now overlooked can be interpreted--the role of the secretary of the colony. The principal artifacts--book presses, documents, desks, and other scriptional material might be effectively displayed and interpreted giving us an added dimension beyond the legislative and judicial branches that we now cover in the capitol.

C.R.L.

The Reconstruction of Williamsburg's First Colonial Capitol, 1928-1934: A Critique

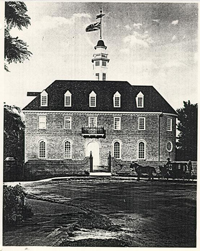

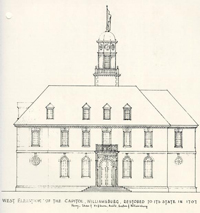

The purpose of this paper is to examine how certain attitudes shaped the design decisions made by the Boston architectural firm of Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn as they worked out the plans for the reconstruction of the first colonial capitol in Williamsburg in the early 1930s (Fig 1). More than any other building in the restored town, the reconstructed capitol symbolized the ideals that motivated John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to underwrite the cost of this monumental undertaking. After the building had been completed in the winter of 1934, it was tempting, Rockefeller mused, to "sit in silence [in the reconstructed building] and let the past speak to us of those great patriots whose farseeing wisdom, high courage and unselfish devotion to the common good will ever be an inspiration to noble living." It was to their memory that the reconstruction of the building, and indeed, the entire restoration of colonial Williamsburg, was "forever dedicated."1

In fact, this reconstructed two-story brick capitol, with its distinctive twin apsidal ends, was not the building that Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, or George Washington ever set foot in during the stirring events of the Revolution. It was a copy of the first building that had been erected under the direction of Governor Francis Nicholson from 1701 to 1705. This earlier building was destroyed by fire in 1747. After some 2 debate as to whether the provincial capital should be moved from Williamsburg to a more central location further west, the General Assembly decided to remain in Williamsburg and rebuild the capitol.

The old brick walls of the first capitol suffered little damage from the fire, but were, nonetheless, taken down and completely rebuilt in 1751. The second capitol was reconstructed on top of the old foundations, the only major exterior changes being the squaring off of the southern apsidal walls and the construction of a two-story portico on the west façade facing the Duke of Gloucester Street (Fig 8). This second building witnessed the dramatic events of the Revolution but was left to neglect after the capital moved west to Richmond in 1780. In 1832 the building suffered the same fate as the first one, falling victim to another fire, followed by demolition. In the mid-nineteenth century, an academy was constructed on the capitol site but was pulled down by the time of the centennial celebration of Washington's victory at Yorktown in 1881. The Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (APVA) acquired the property in 1897, located and marked the outline of the colonial foundations, and erected a monument on the site. In 1928 the APVA deeded the site to Colonial Williamsburg, Inc., with one of the conditions of the gift being that the APVA had to approve the design of the reconstruction before building could begin. Another provision required that the building be completed within five years of the date of the conveyance.2

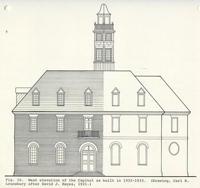

3As early as 1927 members of Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn had produced preliminary sketches of the second capitol with its large two-story portico on the west façade. Despite its valued association with the Revolution, the decision was soon made not to reconstruct this building but the earlier one (Fig. 2). The architects offered a compelling argument for their choice of the first capitol. Whereas considerable documentary evidence survived in the legislative papers of the House of Burgesses and Council describing in great detail the fittings and finishes of the first building, very little material could be found concerning the second structure. The discovery of the Bodleian plate in December 1929 with its north elevational view of the earlier capitol provided an added cache of detailed information concerning the placement and size of door and window openings as well as the general character of the brickwork, central arcade, and cupola (Fig. 3).3 Given this solid base of evidence, the architects, led by principal partner Andrew H. Hepburn, reasoned that there would be less room for conjecture by constructing this first building. They also felt that the H-shaped structure with its apsidal ends was inherently more interesting architecturally.

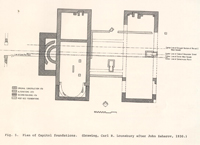

As design of the building proceeded in earnest in 1929, the systematic collection of documentary evidence associated with the capitol was well underway. The research department of Colonial Williamsburg, the architects of Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn, and the APVA capitol committee worked closely to accumulate and interpret all known documents relating to the construction and 4 furnishing of the two capitol buildings. Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, the rector of Bruton Parish Church who had first talked Rockefeller into supporting the idea of restoring and recreating the eighteenth-century buildings in Williamsburg, served as a coordinator of all the various research groups. This effort culminated in 1932 with a two-volume chronologically arranged source book of all the available documentary references concerning the capitol from its first plans in 1699 to the final destruction of the second building in 1832.4 In addition, a second valuable source of evidence appeared in 1928 when the capitol site was excavated by Prentice Duell, Herbert Ragland, Harold Shurtleff, and others under the directions of the architects in the Boston firm (Fig. 4). In 1930 John Zaharov made measured drawings as well as a scale model of the excavated foundations (Fig. 5). He also provided a detailed analysis of the various periods of brickwork and mortar excavated on the site.5 The Bodleian plate combined with contemporary documentary sources and the archaeological evidence provided the architects and the APVA capitol advisory committee with a wealth of information to guide their deliberations. However, as in many restoration projects, there were lacunae and contradictory pieces of evidence which caused considerable confusion and conflicting interpretations among the researchers and architects.

As in their other projects for Colonial Williamsburg, Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn divided the capitol design work between their Boston office and a branch office which had been 5 established in Williamsburg. Andrew Hepburn assumed the task of coordinating the work of both offices from initial designs to completion of the working drawings. Although the final design of the capitol was the product of many talented hands, it was Hepburn who had the primary responsibility of explaining his firm's design decisions to the APVA Capitol Committee. Fully conscious that their mammoth undertaking in Williamsburg had already attracted national attention and that the pioneering work would later be scrutinized by "both historians and architects… in the light of the historic record," Hepburn took great care to produce a final report that carefully outlined the factors that determined their design decisions.6

Throughout 1930 the architects prepared sets of design drawings which were then sent to the APVA committee for review. The committee often invited members of the architectural firm to their meetings to explain design decisions. Despite the amiable relationship that initially characterized the conversations between the architects and the APVA committee, a pronounced conflict between the two began to emerge as each group interpreted the archaeological evidence and documentary sources in light of their own historical and aesthetic prejudices. Both groups endeavored to develop a design for the building that would "conform as nearly as possible with all known facts." Their differences underscored the difficulties and biases inherent in the design and execution of architectural reconstructions, even 6 ones such as the capitol that are blessed with abundant documentary evidence.7

The root of the controversy centered around the placement of the doors on the west and east façades of the building--a sticking point which would have a profound consequence on the overall plan of the building. Serious differences also arose over the character of the colonial work. The APVA committee felt that the architects misinterpreted the meaning of many of the surviving specifications and habitually overestimated the degree and scale of elaboration and finish proposed for the building. Led by historian E. G. Swem of the College of William & Mary and Colonel Samuel Yonge, a retired engineer and a lifelong investigator of early Virginia architecture, the APVA felt that the elaborate designs of architects Robert C. Dean, Thomas Waterman, and Andrew Hepburn did not accord with the economic and social conditions of Virginia in the first decade of the eighteenth century.8 The architects, in turn, argued their case on the basis of their understanding and interpretation of Georgian design principles.

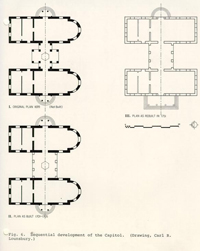

The difficulties encountered by the restoration architects and APVA

committee stemmed in part from some amount of confusion among the

colonial builders themselves. Its evident from the colonial documents

that the design of the building emanated from a committee that

continued to change its mind both before and after construction

began in 1701 (Figs. 6, 7). In 1699, shortly after the decision

was made to move the seat of

7

government from Jamestown to Williamsburg, the General Assembly

passed "An Act directing the building the Capitoll…," which

set out a detailed set of specifications for the new building.9 The act called for a two-story brick building with two seventy-five foot

wings terminated at one end by semicircular apses "made in the forme

and figure  ." The two wings--one for the House of Burgesses, the

other for the General Court--were to be "joyned by a Cross Gallery

of thirty foot long and fifteen foot wide eachway according to

[the

." The two wings--one for the House of Burgesses, the

other for the General Court--were to be "joyned by a Cross Gallery

of thirty foot long and fifteen foot wide eachway according to

[the  ] figure," and "raised upon Piazzas and built as high as

the other parts of the building and the Middle thereof a Cupulo to

surmount the rest of the building" (Fig. 6:I). To provide a prominent,

eye-catching focal point for the two long façades, the specifications

stated that "the midle of the front on each side of the sd building shall

have a Circular Porch wth an Iron Balcony upon the first floor over it &

great folding gates to each porch of Six foot breadth both" (Fig. 11). This first

set of specifications set the general plan from which all future changes would diverge.

] figure," and "raised upon Piazzas and built as high as

the other parts of the building and the Middle thereof a Cupulo to

surmount the rest of the building" (Fig. 6:I). To provide a prominent,

eye-catching focal point for the two long façades, the specifications

stated that "the midle of the front on each side of the sd building shall

have a Circular Porch wth an Iron Balcony upon the first floor over it &

great folding gates to each porch of Six foot breadth both" (Fig. 11). This first

set of specifications set the general plan from which all future changes would diverge.

The General Assembly committee charged with overseeing the construction of the new capitol spent the next two years engaged in the many pursuits necessary before actual construction could begin. In late 1699 it hired Henry Cary, who had just completed the York County Courthouse, to be the project overseer. Cary and the committee soon began the task of finding the necessary materials and workmen to undertake such a substantial commission. Throughout 1700 and well into the next year kiln 8 after kiln of bricks were burned and bricklayers and carpenters imported from England. Materials such as stone, glass, and ironwork which could not be made or obtained in the colony were also purchased and shipped from England.

By the summer of 1701 when actual construction on the site was drawing near, the assembly decided to modify the plan. On August 28th it changed its mind about the arcade that was to connect the two wings and decided that its width should be enlarged from fifteen feet to thirty feet in order to make it "the same breadth the main buildings is" (Fig. 6:II). At the same time, it provided further details about the design of the two porches on the long east and west façades. Each were to "be built Circular fifteen foot in breadth from Outside to Outside" and "stand upon Cedar Collumns."10

These small but important changes significantly transformed the plan

of the capitol. As Marcus Whiffen has argued, the 1701 changes did away

with the cross-shaped gallery intended in the " " plan to intersect in

the center of the connecting arcade. Running parallel with the two major

wings, this small cross-projection may have been intended as a semi-enclosed

lobby entrance and stair tower similar to the arrangement found in many

contemporary buildings.11 For example, both the 1676 statehouse at St. Mary's City,

Maryland, and the 1696 statehouse in Annapolis, built under the direction of Francis

Nicholson when he was governor of Maryland, had front and rear porch towers.12

The members of the colonial building

9

committee presumably felt that the tiny connecting arcade and cross

entrance porches provided little room and its awkward roof form posed

considerable construction problems. Once the idea of the cross-gallery

with its possible stairway to the second floor had been jettisoned, the

function of the original gallery space above the ground floor arcade was

transformed. Instead of a narrow corridor, the thirty by thirty foot space

now turned into a large conference room.13

" plan to intersect in

the center of the connecting arcade. Running parallel with the two major

wings, this small cross-projection may have been intended as a semi-enclosed

lobby entrance and stair tower similar to the arrangement found in many

contemporary buildings.11 For example, both the 1676 statehouse at St. Mary's City,

Maryland, and the 1696 statehouse in Annapolis, built under the direction of Francis

Nicholson when he was governor of Maryland, had front and rear porch towers.12

The members of the colonial building

9

committee presumably felt that the tiny connecting arcade and cross

entrance porches provided little room and its awkward roof form posed

considerable construction problems. Once the idea of the cross-gallery

with its possible stairway to the second floor had been jettisoned, the

function of the original gallery space above the ground floor arcade was

transformed. Instead of a narrow corridor, the thirty by thirty foot space

now turned into a large conference room.13

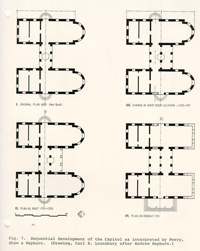

Analysis of the original construction sequence by the architects in Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn's office proceeded under certain mistaken assumptions which ultimately created critical flaws in their final design (Fig. 7). First and foremost was their error in locating the center point of the two long façades on the east and west sides. The architects thought of the principal façade as only the straight section of the wall and disregarded the apsidal projection. In contrast to the APVA committee which maintained throughout the design discussions that the apsidal end was an integral part of the main façade, thus creating a different center point, the architects defined the central axis of the building as being the center point of the shorter flat section of the façade.14 The selection of such a center point allowed the architects to devise a symmetrical composition of door and window openings on this straight façade, an arrangement they considered as absolutely essential to harmonize with early eighteenth-century design principles.

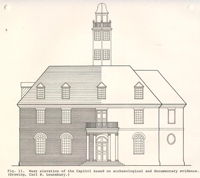

10The consequence of this decision was enormous. It affected the entire design of the building from the placement of the great folding doors called for in the 1699 specifications to the circulation route within the building, the location of the compass-headed windows in these façades, and the treatment of the arcade separating the two wings. It also caused the cupola to be lined up "off-center" from the doorway since the position of the cupola, like the semicircular foundations, was centered on the entire length of the building and not the short fagade.15 The architects were willing to settle for this incongruous asymmetrical arrangement since they believed the cupola was "not a prime factor of this façade" (Fig. 10).16

Part of their reason for centering the door on the straight part of the long façade was based on their reading of the placement of window openings in several nineteenth-century views of the second capitol (Fig. 8). These illustrations of the capitol show a symmetrical façade with three windows on either side of a central pair of doors. Hepburn and his researchers believed that when the building was rebuilt after the 1747 fire, the lower part of the walls of the first building were reused. The openings shown in these illustrations, they thought, indicated the exact position of the windows in the first building with the addition of a new window at the south end where the apse had been pulled down and the wall squared (Fig. 7:IV).17 They also argued that the original position of the door, centered on the straight portion of the first capitol, was moved at some 11 unknown time before the 1747 fire to the center of the entire façade, a position that was retained when the building was reconstructed in 1751 (Fig. 7:III). The original door was converted at the time of this change into a window.

They believed that despite these early changes, the early nineteenth-century illustrations were an accurate guide and solid evidence for their theory about the original symmetrical placement of openings. However, John Blair, a member of the colonial council and the capitol building committee in 1751, kept a diary which refutes this assumption. It is evident from his diary entries that the walls of the first capitol were not partially reused in the second building, but were completely demolished. Although built on the foundations of the first building, the walls of the second capitol were entirely new above ground.18 Thus the information about openings derived from the nineteenth-century illustrations in reality had no bearing on the argument.19

Of far greater importance was the fact that the architects' assumption about the placement of the great west door ignored the archaeological evidence. The 1928 excavations of the capitol site uncovered the remains of a semicircular foundation attached to the west wall of the building that was assumed to be the remains of a porch and steps (Fig. 9). The architects tried hard to play down its significance since it was not located where they had planned to put their front entrance. Rather it was situated within a few inches of the center point of the length of 12 the entire building and more than six feet to the south from the center point of the straight façade.

Because these brick remnants were not where they were supposed to be, the architects found it hard to accept them as original. They argued instead that the semicircular foundations dated from a later period and were therefore not the remnants of the porch called for in the 1699 specifications. John Zaharov, an MIT-trained architect with no previous archaeological experience, reported that the mortar found in the semicircular brickwork did not match that of the principal walls, although he admitted that it was colonial in character and "only slightly inferior" to that found in the main wall. The architects' contention of a later construction date based on differences of colonial materials and workmanship was weakened, however, when Zaharov observed that the bricks of this feature were similar in "color and size to the original ones especially those" found in the west façade wall.20 Apparently the architects also overlooked the fact that the semicircular foundation was bonded into the west façade wall and that there was no evidence for an earlier generation of porch masonry as both photographs and Zaharov's drawing clearly indicate.21 Bonded joints can only be planned for at the time of original construction. The APVA committee found Zaharov's and the architects' arguments less than convincing.22 As Colonel Yonge pointed out, most colonial buildings often showed a great disparity in brick texture, size, and color and mortar composition. He noted that "great 13 uniformity" in production methods was "not the practice at that time."23

The porch projection measured sixteen and a half feet in diameter where it met the west wall of the façade. Because this was a foot and a half wider than the fifteen feet called for in the original General Assembly specifications, the architects tried to dismiss the feature as later since it failed to square with the written record.24 This discrepancy, combined with the difference in mortar composition, was enough evidence for them to maintain that the foundations belonged to a later, though undetermined period. When pressed by the APVA committee to provide evidence for an earlier entrance foundation at the center of the straight façade, the architects offered a reply that was based on a misreading of the language in the colonial documents. In defense of their intention of placing a smaller entrance platform at a place where there was no archaeological evidence, Andrew Hepburn noted that the original specifications for the capitol called for the porches "to rest on cedar posts," which he interpreted not as columns to support an entablature and second floor balcony, but as "underground piles to hold the porches." He reasoned that since these pilings were wooden, they had long since disappeared leaving no archaeological evidence.25 Not only did a lack of evidence not hinder the architects in their determination, it enhanced their argument in favor of locating the entrance porch in the center of the straight façade (Figs. 10, 11).

14With hindsight we can clearly see now that the essential reason for the architects' stubborn and illogical rejection of the compelling evidence was their deeply rooted aesthetic preference for compositional balance and axial symmetry. The primary members of the office had been schooled in these principles at Harvard, MIT, and the Ecole des Beaux Arts. They practiced these concepts in their Colonial Revival designs in the early 1920s.26 Given their background, it was difficult for the members of Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn to conceive of an asymmetrical façade on a major public building in colonial Williamsburg. After all, they could point to the clearly delineated symmetrical fronts on the Wren Building and the Governor's Palace in the Bodleian plate to reinforce their notion that a fully mature and rational, albeit provincial, classicism had evolved in the Virginia capital at the turn of the seventeenth century.

Although their Beaux-Arts design philosophy often colored their view of Williamsburg's colonial architecture, they were not always blinded by it. They did recognize an important distinction between the work of restoring Williamsburg's eighteenth-century buildings and their modern design commissions. Sometimes they suppressed their desire to devise a symmetrical façade or to elaborate an architectural detail in the face of clear documentary or archaeological evidence. In an early design scheme for the ancillary buildings at the Governor's Palace, A. G. Lambert, superintendent of the building of the Governor's 15 Palace and a man who had received training "in the days when the Ecole des Beaux Arts of Paris was thought to be the leading school of architecture," laid out a site plan for the service buildings based on a series of perpendicular and diagonal axes which bore little resemblance to the haphazard character of the archaeological evidence.27 Led by Fiske Kimball, the Advisory Committee of Architects (a panel of nationally-prominent architects called in to review the work of Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn during the early day of the restoration) attacked Lambert's scheme, pointing out that it ignored many buildings which were known to have existed and included others for which there was no evidence.28 With his "old-fashioned ideas of symmetry," Lambert was convinced that colonial builders "wouldn't have scattered these buildings around" in the way the archaeological evidence had clearly revealed.29 In the case of the Palace, the weight of evidence overcame aesthetic preference.

At other times during the restoration evidence took a back seat to philosophy.30 It was ignored especially when it went against the rationale for a design scheme. For example, archaeological investigation of the wall that enclosed the capitol building revealed that the gate pier foundations at the west entrance were on line with the semicircular foundations. The fact that the entrance did not align with the proposed steps and door opening at the center point of the straight façade did not disturb the architects like the "off-center" cupola. Instead, when the time came to draw up a landscape plan for the 16 capitol grounds, they simply angled the pathway from the gate to meet the steps (Figs. 1, 5).

Even Harold Shurtleff, the first director of the research department, who although an architect by training usually argued from points of historical evidence, could be transfixed by the tenets of Beaux-Arts design. After reviewing all the pertinent documents and listening to the arguments of both Hepburn and the architects and Colonel Yonge and the APVA committee, Shurtleff agreed wholeheartedly with the designers. In a passionate letter to Dr. Goodwin, he found it:

inconceivable that any [colonial] architect would have located an entrance in the façade at the point where the circular foundations stand at the time when the façade ended in a rounded apse. To do so would mean that the designers had put their doorway "off center"--since the architectural surface they were treating as a unit of design would not have included the apse and would have been confined to the flat or straight part of the west side--or in other words had introduced an unsymmetrical element into what was otherwise in its conception a completely symmetrical design. This seems to any architecturally trained mind impossible, as architects in 1700 or before were as little likely to do that as architects would be today. Which of course means the [modern] architects who have interpreted the data presented to them in this problem….see no place for the "first period" west entrance except in the middle of the front of the west side. This front does not include--and could not from a designer's point of view--the curved surface of the apse.31

Such an ahistorical point of view presupposed a constant set of design principles intuitively understood and practiced by architects on both sides of the Atlantic during the reign of William and Mary. It also ignored the effect of local conditions on public building. The process of designing and erecting large important buildings on the fringe of empire in 17 Williamsburg in 1700 was far different from practices in London. Shurtleff and members of Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn naturally assumed that the design of the capitol was by an architect who thoroughly understood the principles of Georgian design. Although they could not discover the name of the designer in the records, they were certain that, like the churches built in London in the half century after the great fire of 1666, the major public buildings in Williamsburg were the product of trained hands.32

What they failed to appreciate was the relatively undeveloped nature of the colonial building tradition at the turn of the century when professional architects were unknown, major contractual undertakers only emerging, and the process of erecting monumental buildings just beginning. Rather than the work of one man, the design of the capitol was the result of decisions made over several years by a committee of provincial officials, none of whom had training in architecture. Even the principal undertaker, Henry Cary, had little experience in erecting large buildings since there were so few buildings of any consequence in the colony. After nearly one hundred years of settlement, the Chesapeake landscape was still filled with small impermanent wooden buildings. Only the recently constructed College of William and Mary and a handful of brick churches offered anything approaching the scale of the capitol and these structures had stretched the logistical and artisanal abilities of provincial craftsmen and undertakers.

18By thinking of the capitol as a work of art isolated from geographic and temporal conditions, the architects at Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn failed to perceive the pervasive influence that the local building tradition had on its design. As a result, the desire to have a symmetrical façade unwittingly forced them to compromise the colonial plan. Furthermore the equation of frontier Williamsburg in 1700 with metropolitan London or even later colonial Virginia allowed them to indiscriminately select English and late colonial design sources as precedent for many of the architectural details.33

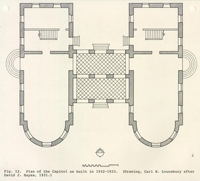

Although they did not divorce the plan from the façade in their design considerations, the architects did follow the Georgian conceit of working from the outside in, making the plan fit the constraints of the symmetrical façade. Placement of the doors at the center of the straight façade meant that the doors opening into the arcade space had to be placed exactly opposite them (Figs. 12, 13). As a result the arcade doors did not stand in the center of the arcade but were off-center several feet to the north. In order to mask this asymmetry, the architects decided to insert an inner set of arches in the center of the arcade, breaking the area up into two distinct fifteen-foot wide spaces. Despite the lack of archaeological evidence for this inner arcade, the architects argued otherwise. They believed that when the colonial builders changed their specifications in 1701 to widen the connecting arcade, the building was already under construction with the two northern most sets of arches in 19 place (Fig. 7:II). The third set of arches to the south was added later in order that the arcade roof could be raised to the same height as the main building.34

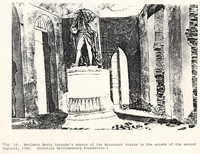

The architects also argued for the presence of an inner arcade based on their interpretation of a drawing made by the architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe in 1796. Latrobe sketched the statue of Lord Botetourt erected in the arcade of the second capitol in the early 1770s (Fig. 14). The sketch shows the statue standing headless in the center of the arcade with brick rubble scattered about the base. The arcade walls are plastered with evidence that the arches had been enclosed at one time. Because Latrobe had incorrectly scaled the arcade space making it seem narrower than it was, Hepburn and the restoration architects thought that this view represented only the two northern arcades, the third one, to the south, being out of view. However, from the angle of the sunlight streaming in from the south, it is evident that there is no third set of arches.35 Furthermore, the fact that the arcade was completely rebuilt in the early 1750s during the construction of the second capitol made Hepburn's argument meaningless.

This error in door placement also affected the layout of the General Courtroom and the House of Burgesses. Located in the center of the straight façade, the doors opened at the back of each room, close to the brick partition walls that separated the stair passages from these main rooms. The architects reasoned that such a position was appropriate for the General 20 Courtroom since it kept people away from the center of activity. Their assumption totally ignored local courtroom design precedent. In many of the county courthouses erected in Virginia in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, rectangular-shaped courtrooms with entrance doors on the two long walls were quite common. These doors were generally located close to the bar or front of the courtroom near the magistrates' bench rather than at the back of the courtroom. Rather than keep people away from the bench--the locus of court day activity--the proximity of door to bench allowed them to be directly cognizant of the magistrates on their raised platform. Since the restoration architects had not studied colonial courtroom design, they missed this direct reference to local custom employed by the colonial designers.

Coupled with the abstract formality that permeated their design rationale, the restoration architects had a tendency to embellish many of the ornamental details far beyond what the APVA committee felt appropriate. Once again, the source of the conflict emanated from two different perceptions of the state of colonial society at the beginning of the eighteenth century. E. G. Swem and Colonel Yonge proceeded very cautiously in assessing the cultural and economic achievements of the colony. On the other hand, the architects freely adopted ornamental details from many of the grander buildings in England. Their design for the iron balconies above the problematic front doors derived from Hampton Court. The full length panelling of the General 21 Courtroom (Fig. 15) was inspired by that found at the Governor's House at Chelsea Hospital and Glemham in Suffolk. While other details were based on examples closer to home, many were taken from the largest plantation houses built by Virginians two and three generations after the capitol was constructed. The pilasters for the House of Burgesses were modeled after those at Gunston Hall built in the late 1750s. The spandrels in the capitol stairways were patterned after those at Kenmore in Fredericksburg erected in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. The pedimented doorway in the capitol stair hall derived from the 1770s woodwork at Shirley in Charles City County.36 Although the chronologies of many of these Virginia houses were unclear to the restoration architects in the 1930s, all were built at times far different than when the capitol was under construction. From the 1730s through the Revolution, some Virginians built on a scale and in stylish sophistication that was unknown to their forefathers at the beginning of the century.

The use of anachronistic precedent cannot always be avoided. However, the restoration architects' choice of the best architectural examples that colonial Virginia and Georgian England had to offer was almost inevitable. Their aesthetic inclination was toward the well-crafted and grandiose. Their partiality for the genteel and urbane is exemplified by the design of the panelling for the General Courtroom. In 1703 the committee appointed by the General Assembly to oversee the construction of the capitol issued a set of instructions for the 22 furnishing of the courtroom. Their specifications called for "the Circular part thereof to be rais'd from the seat up to the windows."37 Reviewing the document in 1930, the restoration architects could make no sense of the statement and dismissed it as being "practically meaningless."38 What they failed to understand about this elliptic phrase was that the word "panelling" had been omitted from a sentence that was intended to read, "the Circular part thereof to be rais'd 'panelling' from the sat up to the windows."39 As was typical of county courthouses of the period, the committee members had intended only for the apsidal part of the courtroom where the magistrates sat to be panelled the three and a half or four feet between the top of the justices' bench and the lower part of the windows.40 Based on a 1705 specification for the "wanscote" to be painted "Like Marble," the restoration architects decided to construct floor to ceiling panelling with Ionic pilasters throughout the entire courtroom. They pointed out that the term "wainscot" in the eighteenth century could be applied to all heights of wooden panelling and felt justified in extending the rich panelling throughout the room (Fig. 15). The splendid woodwork is far richer than any found in contemporary English courtrooms. As reconstructed, it makes nonsense of the visual contrast intended by the colonial builders between an ornamented bench and a much plainer public space.

Colonel Yonge continually questioned the architects' propensity to embellish the capitol. When the architects' 23 proposed an elliptically-shaped council chamber above the General Court (Fig. 16), the APVA balked. They accepted the necessity of repeating the semicircular form at the south end of the room above the apse, but saw no need for it to be repeated at the north end. Hepburn admitted that although elliptical rooms did not come into general use in England and America until much later, prototypes could be found in the work of Inigo Jones and Christopher Wren in London in the seventeenth century.41 Colonel Yonge criticized such pretentious precedents as being out of context, arguing that "the embellishments of the large rooms of the old Capitol, as proposed by the architects, is not believed to accord with the then rural environment and the undeveloped condition of the country at large with its sparse population, still new country and almost a wilderness, or in keeping with the scant means available for any greater expenditure than actually necessary."42

In the end the persistence of the architects paid off. Colonel Yonge was unable to persuade his fellow members on the APVA committee to his point of view. Where argument failed, the fine quality of Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn's presentation drawings and scale model of the reconstructed capitol proved convincing. The wholehearted endorsement of the architects' design by the Advisory Committee of Architects did much to mollify lingering concerns held by some members of the APVA.43 With few revisions, the APVA Capitol Committee gave final approval of the architects' 24 designs at the end of 1930 and construction began in October 1931.44

Work progressed smoothly over the next two years as the contractors and an army of skilled craftsmen carefully followed dozens of detailed drawings ranging from mechanical systems to royal coats of arms produced by Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn's office (Fig. 17). When Rockefeller dedicated the building in early 1934, he could be truly proud of the fine craftsmanship found throughout the building. The complicated composition of the raised panelling of the General Courtroom was perfectly balanced, the turned stair balusters carefully matched, and the Flemish bond brickwork with glazed headers glistened in the sunlight in formulaic regularity.

This regularity of detail and perfection of ornament was typical of the Colonial Revival style in which every last detail was carefully resolved on paper before the work of the joiner and bricklayer ever began. The competence of the craftsmen who worked on the capitol in the early 1930s probably surpassed many of the skills of their colonial predecessors.45 However, the precision of the design details of the reconstructed capitol belies the realities of the colonial construction process. That process was much less structured and far more diffuse than the restoration architects understood. Throughout the eighteenth century, the division between the design stage and actual construction was often blurred. Like the eighteenth-century capitol planners, colonial building committees continued 25 to design various features of their buildings and resolve various details after construction had begun. In many cases, committees changed their minds and decided to extend the length of a building, add a new door or an extra window after the walls were already up. Rough sketches of plans and elevations often served as the only formal drawings a committee ever produced, leaving the more detailed matters to be worked out by undertakers and principal craftsmen. As a result, awkward solutions occasionally appear in the fabric of colonial buildings. Break joints in foundation walls suggest a change in plan; the edges of door moldings run into cornices, walls, and stairs; uneven and asymmetrical panelling adorn many walls; and Flemish bond brickwork is punctuated by make-up bricks between openings and at edges. Quirks abounded; regularity was illusionary.

All of this was missed by the restoration architects in their work on the capitol restoration. Like Rappacinni's daughter, perceived perfection would never stand close scrutiny. Caught in their aesthetic predilections, they missed the spirit of the colonial building process. Although the capitol is a testament to the architects' skills in the handling of eighteenth-century details, it now stands as a monument to a past age, telling us as much about the 1930s as the colonial period.

Despite the inherently conservative nature of American history museums, their purpose in the past seventy years has changed almost as rapidly as the sartorial fashions displayed in many of their exhibitions. The period room filled with fine panelling, exquisite Chippendale furniture, and Copley portraits 26 representing the genteel culture of the colonial past is as much a relic of the 1920s as the Model T, bobbed hair, and the raccoon coat (Fig 18). Dirt floors, squealing pigs, and first person interpreters plying the new social history to bell-bottomed visitors clearly marked a new era in museology in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Spurred by scholars asking a different set of questions of the past, many museums changed their interpretations to suit the needs of a new generation of museum-goers. The views of colonial culture presented by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation or Plimoth Plantation in the 1980s is far different from those visitors received decades earlier.

Many older institutions are saddled with the relics of earlier museum ideals and attitudes. A museum that has had a long history of collecting nothing but the best pieces of Philadelphia cabinetwork finds that it has a surplus of highboys when it begins to interpret the daily life of ordinary colonial Americans. Many institutions must also come to terms with buildings once lovingly restored or reconstructed, which now fit less comfortably into new interpretative programs. It is far easier to hide unwanted furniture than it is to deal with a large house that has been scraped and improved in an earlier restoration.

Just as the educational goals of history museums have changed so too has our perspective of the architectural legacy of early America. Brick plantation houses and even the more modest frame structures that line the streets of Williamsburg, once 27 thought typical of Chesapeake architecture, are now seen by architectural historians as extraordinary survivors, far larger and more elaborate than the housing inhabited by most colonial Virginians.46 The members of the Perry, Shaw, & Hepburn firm who transformed the rundown town of Williamsburg into the museum showpiece of colonial culture, labored under a far different set of assumptions about the buildings they were restoring than do their present day successors.

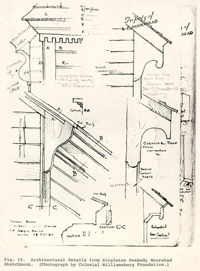

Trained in the Beaux-Arts principles of design and versed in the Colonial Revival style, the first restoration architects in Williamsburg had a strong knowledge of eighteenth-century stylistic details but only an imperfect understanding of how those various elements fit together in an hierarchical system of design. In the field they carefully sketched the profile of door and window moldings, but failed to note the relationship of these decorative elements to other details in a particular room or throughout the building (Fig. 19). As we have seen, typical too of this early generation of pioneer restorationists was the tendency to search out and record the best examples of colonial architecture rather than the mundane and ordinary. As a result of their extraordinary effort and the fine craftsmanship that went into the restoration and reconstruction of buildings like the capitol, the museum's visitors are presented with a more generous and genteel view of colonial building standards than had once existed.

28How does a museum deal with the legacy of its early history, especially when the historical and architectural underpinnings that sustained its early development have shifted? Do we preserve buildings, exhibitions, and interpretive programs as they were first created and view and treasure them like some old textbook as a record of an earlier generation's perception of the past? Do we respond to changing intellectual fashion and new high-tech exhibition techniques by casting off or revamping their work? Although such questions admit no easy answers, it is incumbent for each new generation to carefully study the methodological practices and philosophical principles that guided earlier restorations and exhibitions.

Footnotes

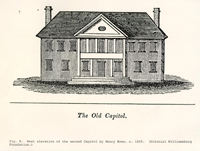

29 Fig. 1. West elevation of the Capitol. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, c. 1935.)

Fig. 1. West elevation of the Capitol. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, c. 1935.)

Fig. 2. Preliminary design for the Capitol. (Drawing, Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, 1929.)

Fig. 2. Preliminary design for the Capitol. (Drawing, Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, 1929.)

Fig. 3. North elevation of Capitol, Bodleian Plate, c. 1737. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Fig. 3. North elevation of Capitol, Bodleian Plate, c. 1737. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Fig. 4. Excavation of the Capitol site. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1928.)

Fig. 4. Excavation of the Capitol site. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1928.)

Fig. 5. Plan of Capitol foundations. (Drawing, Carl R. Lounsbury after John Zaharov, 1930.)

Fig. 5. Plan of Capitol foundations. (Drawing, Carl R. Lounsbury after John Zaharov, 1930.)

Fig. 6. Sequential development of the Capitol. Drawing, Carl R. Lounsbury.)

Fig. 6. Sequential development of the Capitol. Drawing, Carl R. Lounsbury.)

Fig. 7. Sequential development of the Capitol as interpreted by Perry, Shaw & Hepburn. (Drawing Carl R. Lounsbury

after Andrew Hepburn.)

Fig. 7. Sequential development of the Capitol as interpreted by Perry, Shaw & Hepburn. (Drawing Carl R. Lounsbury

after Andrew Hepburn.)

Fig. 8. West elevation of the second Capitol by Henry Howe, c. 1845. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Fig. 8. West elevation of the second Capitol by Henry Howe, c. 1845. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Fig. 9. Foundation of the semicircular west porch. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Fig. 9. Foundation of the semicircular west porch. (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Fig. 10. West elevation of the Capitol as built in 1932-1933. (Draawing, Carl R. Lounsbury

after David J. Hayes, 1931.)

Fig. 10. West elevation of the Capitol as built in 1932-1933. (Draawing, Carl R. Lounsbury

after David J. Hayes, 1931.)

Fig. 11. West elevation of the Capitol based on archeaological and documentary evidence. (Drawing, Carl R. Lounsbury.)

Fig. 11. West elevation of the Capitol based on archeaological and documentary evidence. (Drawing, Carl R. Lounsbury.)

Fig. 12. Plan of the Capitol as built in 1932-1933. (Drawing, Carl R. Lounsbury after David J. Hayes, 1931.)

Fig. 12. Plan of the Capitol as built in 1932-1933. (Drawing, Carl R. Lounsbury after David J. Hayes, 1931.)

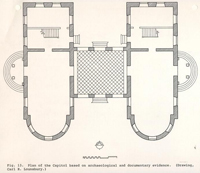

Fig. 13. Plan of the Capitol based on archaeological and documentary evidence. (Drawing, Carl R. Lounsbury.)

Fig. 13. Plan of the Capitol based on archaeological and documentary evidence. (Drawing, Carl R. Lounsbury.)

Fig. 14. Benjamin Henry Latrobe's sketch of the Botetourt statue in the arcade of the second Capitol, 1796.

(Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Fig. 14. Benjamin Henry Latrobe's sketch of the Botetourt statue in the arcade of the second Capitol, 1796.

(Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Fig. 15. General courtroom. (Photograph by F.S. Lincoln.)

Fig. 15. General courtroom. (Photograph by F.S. Lincoln.)

Fig. 16. Council Chamber. (Photograph by F.S. Lincoln.)

Fig. 16. Council Chamber. (Photograph by F.S. Lincoln.)

Fig. 17. Capitiol under construction, 1933. (Photograph by F.R. Nivison.)

Fig. 17. Capitiol under construction, 1933. (Photograph by F.R. Nivison.)

Fig. 18. State dining room, Governor's Palace, Williamsburg. (Photograph by T.L. Williams.)

Fig. 18. State dining room, Governor's Palace, Williamsburg. (Photograph by T.L. Williams.)

Fig. 19. Architectural details from Singleton Peabody Moorehad Sketchbook.

(Photograph by Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Fig. 19. Architectural details from Singleton Peabody Moorehad Sketchbook.

(Photograph by Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)